My 5 week expedition to Manu in the Peruvian Amazon Rainforest with the British Exploring Society

July - August 2015

Our

Journey to The Manu National Park in the Peruvian Amazon Rainforest.

This amazing adventure began when 52 Young Explorers, 8 Trainee Leaders and 10 leaders assembled at Heathrow airport on 23rd July 2015. It was a long flight to Cusco, via Bogota in Colombia and Lima, the capital of Peru. Three days in Cusco, the historical capital of the Inca Empire and now a world heritage site, were very welcome to help us recuperate from the journey, and to acclimatise to an altitude of 3,400m above sea level. We enjoyed the chance to explore Cusco’s markets, visit the Inca ruin of Saqsaywaman, and sample some Peruvian cuisine.

This amazing adventure began when 52 Young Explorers, 8 Trainee Leaders and 10 leaders assembled at Heathrow airport on 23rd July 2015. It was a long flight to Cusco, via Bogota in Colombia and Lima, the capital of Peru. Three days in Cusco, the historical capital of the Inca Empire and now a world heritage site, were very welcome to help us recuperate from the journey, and to acclimatise to an altitude of 3,400m above sea level. We enjoyed the chance to explore Cusco’s markets, visit the Inca ruin of Saqsaywaman, and sample some Peruvian cuisine.

At 3:30am on the fourth day

in Peru, we set off in minibuses, travelling in convoy along the long,

precarious and sinuous road over the Andes. In places the road disappeared due

to rock falls and landslides, with a steep drop to the bottom of the valley on the

other side of the track. As we travelled through Andean mountain villages, we

caught glimpses of local life. We travelled over rocky, dusty passes and saw

Inca burial sites, then over a rackety bridge comprising of a couple of planks across

a steep ravine, until we eventually started to gradually weave our way down

through the cloud forest and into the Amazon basin, to reach the tiny port of

Atalaya (around 500 m over sea).

Following a very brief lunch break of

salty chicken and rice, we transferred to several large, motorised canoes, and

enjoyed an hour-long journey downstream, along the Rio Madre de Dios.

The Penthouse Suite

The Penthouse Suite

Basecamp

Upon reaching the edge of the Manu Learning Centre Reserve, we disembarked on a small stretch of pebbly beach, then had a 20 minute climb through jungle to basecamp. Basecamp was divided into small clearances in the jungle, linked by paths, with each fire occupying a compartment. A fire, of which there were 5, is British Exploring’s term for a group of explorers who live and work together throughout the course of the expedition. My fire, Taramandua fire, was made up of 10 Young Explorers, a Trainee Leader and two leaders. Our camp comprised of 6 tents and 6 hammocks (with a long trail of leaf-cutter ants winding through the middle of it). It was frequently referred to as the penthouse suite because of its stunning view over the Rio Madre de Dios. Other parts of the camp included camps for the other fires, a kitchen area, a science tent, food storage and a medical area, as well as several toilet pits and a waste food disposal area.

During the first few days at basecamp, we tried to acclimatise to a temperature of 30°C in the shade and high humidity, and attempted to get swiftly into camp routine. Since sunrise was at 6:00am, and sunset was at 5:30 pm, it really was a case of “early to bed and early to rise”.

Each fire had a duty day every 3 days, which involved remaining at basecamp to do the cooking (sometimes for around 80 people), collecting water, checking butterfly traps and keeping base camp organised. During the first few days we also listened to induction talks, built furniture such as benches, table and washing stand for our camp, went on practice treks to get a feel for the terrain, as well as experiencing the excitement of a night walk.

Upon reaching the edge of the Manu Learning Centre Reserve, we disembarked on a small stretch of pebbly beach, then had a 20 minute climb through jungle to basecamp. Basecamp was divided into small clearances in the jungle, linked by paths, with each fire occupying a compartment. A fire, of which there were 5, is British Exploring’s term for a group of explorers who live and work together throughout the course of the expedition. My fire, Taramandua fire, was made up of 10 Young Explorers, a Trainee Leader and two leaders. Our camp comprised of 6 tents and 6 hammocks (with a long trail of leaf-cutter ants winding through the middle of it). It was frequently referred to as the penthouse suite because of its stunning view over the Rio Madre de Dios. Other parts of the camp included camps for the other fires, a kitchen area, a science tent, food storage and a medical area, as well as several toilet pits and a waste food disposal area.

During the first few days at basecamp, we tried to acclimatise to a temperature of 30°C in the shade and high humidity, and attempted to get swiftly into camp routine. Since sunrise was at 6:00am, and sunset was at 5:30 pm, it really was a case of “early to bed and early to rise”.

Each fire had a duty day every 3 days, which involved remaining at basecamp to do the cooking (sometimes for around 80 people), collecting water, checking butterfly traps and keeping base camp organised. During the first few days we also listened to induction talks, built furniture such as benches, table and washing stand for our camp, went on practice treks to get a feel for the terrain, as well as experiencing the excitement of a night walk.

The Community Phase

After acclimatisation and training, Taramandua went to Salvacion, the capital of the Manu region, with a population of 3,000. To reach Salvacion, we travelled by boat and then hiked the remainder of the way.

Historically, it has been extremely difficult for the people of Salvacion to derive a livelihood from the land, as soil quality on the floodplains of the Rio Madre de Dios is poor. Therefore to date, the population has relied heavily on non-sustainable living practices, and all their food has been transported along the lengthy and unreliable route from Cusco, which is costly. The population has also carried out destructive forms of employment such as mining and logging.

Biogardens and compost sheds.

The CREES Foundation therefore started an initiative to help the population of Salvacion to live more sustainably. One of its initiatives has been to build biogardens for families who can prove they are trying to live sustainably. These biogardens enable them to provide food for themselves, thereby helping to reduce the malnourishment which is rife in the area, to provide food for CREES (a way to pay off the help given by CREES in building the biogarden), and also to sell excess produce to provide themselves with an income (and reduce their need to log and mine).

During the community phase of the expedition, we built a biogarden for a family living on the edge of the town. This involved clearing the area of unwanted plants whilst leaving the heirloom chilli plant, and constructing a framework to provide a roof to give protection from both sun and rain, and the construction of rows of beds for planting. We also built compost sheds for the community, including one for the local school. It was extremely difficult and tiring work in the heat and sun, but rewarding knowing we were helping to improve the lives of the local community.

After acclimatisation and training, Taramandua went to Salvacion, the capital of the Manu region, with a population of 3,000. To reach Salvacion, we travelled by boat and then hiked the remainder of the way.

Historically, it has been extremely difficult for the people of Salvacion to derive a livelihood from the land, as soil quality on the floodplains of the Rio Madre de Dios is poor. Therefore to date, the population has relied heavily on non-sustainable living practices, and all their food has been transported along the lengthy and unreliable route from Cusco, which is costly. The population has also carried out destructive forms of employment such as mining and logging.

Biogardens and compost sheds.

The CREES Foundation therefore started an initiative to help the population of Salvacion to live more sustainably. One of its initiatives has been to build biogardens for families who can prove they are trying to live sustainably. These biogardens enable them to provide food for themselves, thereby helping to reduce the malnourishment which is rife in the area, to provide food for CREES (a way to pay off the help given by CREES in building the biogarden), and also to sell excess produce to provide themselves with an income (and reduce their need to log and mine).

During the community phase of the expedition, we built a biogarden for a family living on the edge of the town. This involved clearing the area of unwanted plants whilst leaving the heirloom chilli plant, and constructing a framework to provide a roof to give protection from both sun and rain, and the construction of rows of beds for planting. We also built compost sheds for the community, including one for the local school. It was extremely difficult and tiring work in the heat and sun, but rewarding knowing we were helping to improve the lives of the local community.

Whilst working in the town, we stayed in a

government run hostel, which was an experience in itself, firstly as initially

there wasn’t a bed for me, so I slept on the floor amongst the cockroaches, but

also because breakfast involved taking our mess-tins to the “reception” for hot

water to stir in our porridge oats! Staying in the town also meant that we

could visit some of the town’s eateries to try some local dishes, including the

dubious chicken foot soup. One evening we enjoyed a game of football against

the local people, with us clad in our explorer gear and wellies! The locals won

the match quite conclusively.

A Banana Plantation

After 5 days, we moved out of the town for camping in what we referred to as “Bullet Ant Camp”, as Bullet Ants were everywhere (these ants are famous for having the most painful sting of any insect in the world, and some liken the pain to being shot). Our role here was on the banana plantation to plant Kudzu, a legume which helps control erosion after deforestation, improve soil quality, and reduces the impact of weeds. This allows the farmers more time to care for the banana plants.

A Banana Plantation

After 5 days, we moved out of the town for camping in what we referred to as “Bullet Ant Camp”, as Bullet Ants were everywhere (these ants are famous for having the most painful sting of any insect in the world, and some liken the pain to being shot). Our role here was on the banana plantation to plant Kudzu, a legume which helps control erosion after deforestation, improve soil quality, and reduces the impact of weeds. This allows the farmers more time to care for the banana plants.

We helped two local ladies with this work. They used machetes

to clear the ground of the dense undergrowth, and we planted the seeds. This

work was in difficult terrain, and extremely tedious. We all struggled at this

stage, as we were hampered either by heat and sun or heavy downpours and cold

when el Friaje struck. It was miserable to wake up soggy after a night in a wet

tent and continually have to put our feet into wet socks and wellies at the

start of a new day; many in our fire were also hampered by a stomach sickness

as well.

The Science and Adventure Phase

Upon returning to basecamp on the other side of the river, we were itching to start the science part of the expedition, which would help CREES with their ongoing research into the area. Our fire undertook quite a lot of palm surveys at various altitudes, as one member of our fire proved to be quite an expert in botanical identification. We did these whilst trying to conquer the infamous Pini-Pini ridge, which includes both the peaks of Pini A and Pini B, at over 1,100m above sea level. I preferred Pini B, as there was cloud forest at its summit. This had a silent and mystical quality and lacked the incessant insect noise we had experienced elsewhere in the rainforest. The air felt clean, damp and earthy and the ground was soft underfoot, and mosses and ferns coated everything. On returning to England, the botanical expert in our fire discovered he had photographed 2 extremely rare Begonia species: Begonia subspinulosa and Begonia altoperuviana in this part of the forest.

Upon returning to basecamp on the other side of the river, we were itching to start the science part of the expedition, which would help CREES with their ongoing research into the area. Our fire undertook quite a lot of palm surveys at various altitudes, as one member of our fire proved to be quite an expert in botanical identification. We did these whilst trying to conquer the infamous Pini-Pini ridge, which includes both the peaks of Pini A and Pini B, at over 1,100m above sea level. I preferred Pini B, as there was cloud forest at its summit. This had a silent and mystical quality and lacked the incessant insect noise we had experienced elsewhere in the rainforest. The air felt clean, damp and earthy and the ground was soft underfoot, and mosses and ferns coated everything. On returning to England, the botanical expert in our fire discovered he had photographed 2 extremely rare Begonia species: Begonia subspinulosa and Begonia altoperuviana in this part of the forest.

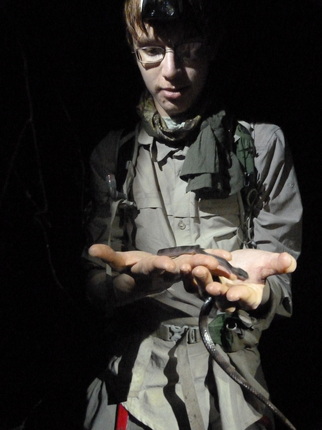

The night walks were extremely popular, as this was

when most of the jungle creatures erupt into life. As we walked in single file,

the night sounds engulf us in their intensity, whilst our head torches

strengthened the vivid jungle colours. We were looking for glimmers of eye

shine, to spot the creatures of the night in the dense tangle of vegetation.

Many exciting species of insects, spiders, snakes and frogs were seen and

photographed. My proudest find was the discovery of a young glass frog, Teratohyla midas, an indicator

of environmental changes and water impurities due to their sensitivity and thin

skin.

We also identified nocturnal bird calls, and enjoyed

listening to the chirpings of the night monkeys, though these were particularly

hard to spot. Even more exciting were two sightings of the deadly and rarely

encountered Bushmaster snake (Lachesis

muta) – one of these was 2.1m long, and was found in Taramandua’s

penthouse suite. This provided an interesting wake up call, and resulted in a

camp evacuation!

Another successful, useful and extremely interesting

activity was to set camera traps, which photographed, amongst other things,

jaguars, an ocelot, tapirs and peccaries. Other projects included using traps

to catch butterflies and moths for identification and counting, riverbed transects,

birdwatching sessions and making casts of animal prints with wax. I enjoyed the

colourful spectacle at the clay lick, where Parakeets, Parrots and Macaws visit

early every morning to gain nutrients from the clay.

On the final day we had a Bioblitz competition to

identify as many species as possible within a 24 hour period. Taramandua won

this, and we were awarded a gold crown which we took turns in wearing on the

journey home.

Over the course of the time in the jungle, I saw many amazing species, all of which are things you normally only ever see on nature documentaries: monkeys (Spider, Capuchin, Squirrel and Woolly), Hummingbirds, enormous spiders like Tarantulas and deadly Brazilian Wandering Spiders, a Poison Dart Frog, Peccaries, large and colourful moths and butterflies, ornate birds including the lovely Macaws, Parakeets, Parrots and Hoatzin, and a host of the most impressive, colourful and spiky caterpillars that look like pieces of artwork.

Over the course of the time in the jungle, I saw many amazing species, all of which are things you normally only ever see on nature documentaries: monkeys (Spider, Capuchin, Squirrel and Woolly), Hummingbirds, enormous spiders like Tarantulas and deadly Brazilian Wandering Spiders, a Poison Dart Frog, Peccaries, large and colourful moths and butterflies, ornate birds including the lovely Macaws, Parakeets, Parrots and Hoatzin, and a host of the most impressive, colourful and spiky caterpillars that look like pieces of artwork.

Returning home

Of course, it was eventually time to start to leave this remote and untouched part of the world, and head for home. Although tinged with sadness to be leaving this beautiful place, I was longing for a shower and excited at the prospect of being with family again. The route we took back to Cusco was fairly similar to that we arrived on, but with a few diversions along the way (presumably due to rock falls!). Back in Cusco we spent a day processing the scientific data we had collected and visiting local markets for souvenirs to take home.

Of course, it was eventually time to start to leave this remote and untouched part of the world, and head for home. Although tinged with sadness to be leaving this beautiful place, I was longing for a shower and excited at the prospect of being with family again. The route we took back to Cusco was fairly similar to that we arrived on, but with a few diversions along the way (presumably due to rock falls!). Back in Cusco we spent a day processing the scientific data we had collected and visiting local markets for souvenirs to take home.

General

I loved being in the jungle, but was surprised by how extreme the jungle environment actually was, and it made for a challenging expedition. We were walking in the heat, in extremely difficult terrain, frequently on steep slippery slopes, especially after rainfall. It was determined quite early on by both leaders and Young Explorers that the conditions were just too extreme and dangerous for us to be able to safely complete the expedition section of our Gold Duke of Edinburgh Awards as we had planned. Another aspect to the expedition was how wet it could be, both in terms of the heavy downpours and sometimes we walked at waist height through rivers, which meant that our wellington boots became wet at an early stage, and were slow to dry in jungle conditions. We were warned in advance by British Exploring that we would wake-up each morning to the prospect of putting on wet clothes and although this felt pretty grim and uncomfortable, I soon became used to this. Other hardships were the insect bites and stings, so the application of large quantities of insect repellent seemed to be part and parcel of the jungle experience.

I loved being in the jungle, but was surprised by how extreme the jungle environment actually was, and it made for a challenging expedition. We were walking in the heat, in extremely difficult terrain, frequently on steep slippery slopes, especially after rainfall. It was determined quite early on by both leaders and Young Explorers that the conditions were just too extreme and dangerous for us to be able to safely complete the expedition section of our Gold Duke of Edinburgh Awards as we had planned. Another aspect to the expedition was how wet it could be, both in terms of the heavy downpours and sometimes we walked at waist height through rivers, which meant that our wellington boots became wet at an early stage, and were slow to dry in jungle conditions. We were warned in advance by British Exploring that we would wake-up each morning to the prospect of putting on wet clothes and although this felt pretty grim and uncomfortable, I soon became used to this. Other hardships were the insect bites and stings, so the application of large quantities of insect repellent seemed to be part and parcel of the jungle experience.

All photographs and text © Angus Malmgren